Empowering Brain Cancer Patients Through Knowledge

January 24, 2014

Found in BC Cancer Research Centre, BrainCare BC, Innovation

Today, I’d like to share two patient stories that have had an impact on the direction of brain cancer research and care in B.C.:

About 15 years ago a young man from Whistler, in his late 20s, was struck down by a malignant glioma. I operated on him several times trying to stay ahead of the advancing cells. This was before there was any useful chemotherapy agent to treat brain cancer – just surgery, radiation and the hope of a new experimental drug on the horizon. It was in the days when today’s standard therapy, Temozolomide, was ‘an experimental’ drug, only available by special access or participation in a clinical trial. It’s not hard to imagine the frustration and desperation of the young man’s family; after all these year I can vividly recall the man and his parents and the dynamics of our relationship.

One of our most compelling discussions surrounded the difficulty in gaining access to ‘experimental drugs’ for brain cancer and the logistics of getting new drugs approved. He passed away long before the availability of the current chemotherapy options. I specifically remember having to explain the rationale behind cautious approval of new drugs to parents who had just lost a son. I felt their anger at a world where a young man couldn’t even get a fighting chance. I felt like I was on the wrong side of the battle.

And I remember seeing him regularly, walking along 10th avenue between the BC Cancer Agency and the cancer lodge during the long six weeks of radiation. He was always smiling, a bit bashful, unassuming and never complaining. He was not a ‘curse the darkness’ kind-of-guy, he was a ‘light-a-candle’ kind of guy. Is it me, or does cancer seem to hit the nicest people?

~~

A young mother from Vancouver was skiing with her family in Kelowna and suffered a seizure. They made it back to Vancouver with an appointment to see me. She was found to have a malignant tumour embedded in the speech area of her brain. The surgery went extremely well and in fact the tumour looked to be very compact – it wasn’t the usual diffusely invasive nest of cells I usually encounter. As such it came out very ‘cleanly’ and I was overly optimistic – I told her I ‘took it all out’. Of course she was thrilled.

But the cancerous nature of the tumour necessitated chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Immediately after her first appointment at the BC Cancer Agency she came steaming back to my office, without an appointment – she needed to see me right away.

She was in tears, feeling anger, disappointment and heart-broken. While I had told her that the tumour was removed, a new doctor told her that no, in fact there were still cancer cells in her brain; and these cells would most likely cause her death in 18 months.

Through sobs she asked how I could have misled her the way I did; how could I undermine the trust she had put in me. Why would I do that?

~~

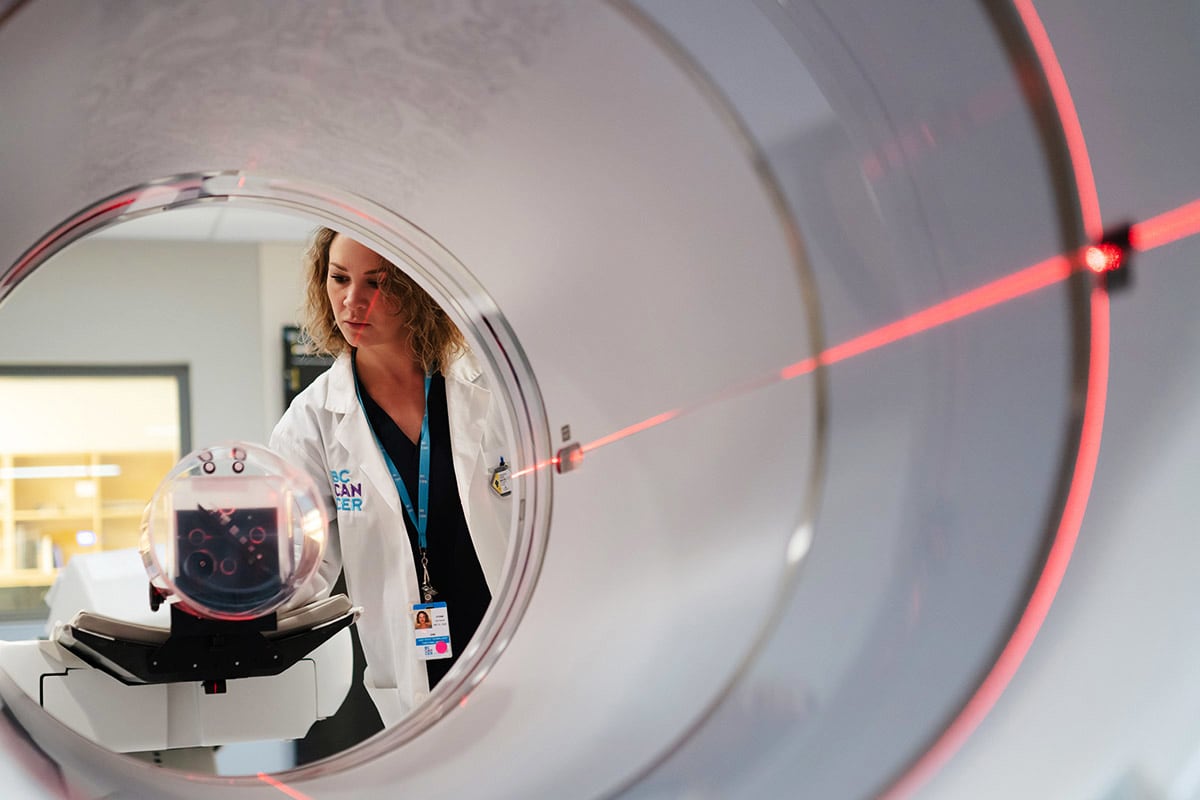

Those are but two stories I carry with me every time I walk into the examining room as a new doctor to meet a patient waiting to hear if their tumour is operable or not, every time I walk into the waiting room after an operation to explain what I did and how the surgery went, and every time I sit down and explain what the pathology result is and what it means. Perhaps most significantly, I carry these stories with me every time I go to the BC Cancer Agency Research Centre as Director of BrainCare.

In the next post I will explain how these stories have given direction to the BrainCare research to cure brain cancer: creative strategies developed at the BC Cancer Agency are helping to quickly identify new treatment options personalized to the individual, and avoid lengthy delays in access. I will also describe a process designed at the BC Cancer Agency to ensure that information about brain tumours is accurately and thoroughly presented to patients, to prevent misunderstandings and ensure that ‘empowerment by knowledge’ takes place.

Thanks for reading,

Brian