Ambassadors of Culture and Care

June 20, 2022

On National Indigenous Peoples Day, we’re highlighting the contributions of Indigenous Patient Navigators — ambassadors of BC Cancer’s Indigenous Cultural Safety project, proudly supported by the BC Cancer Foundation — and the impact they’re having on improving the cancer journey for First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples in B.C.

Smudging, a ceremony using the sacred smoke of burning sage, cedar or sweetgrass to cleanse and clear negative energy, is not something most oncologists prescribe. But it’s exactly the kind of culturally relevant support that Indigenous Patient Navigators (IPNs) at BC Cancer are making space for to improve the Indigenous patient experience.

BC Cancer data shows that Indigenous people, specifically First Nations, are less likely to survive a cancer diagnosis, and experience higher incidences of cervical and colorectal cancer compared to non-First Nations. This could be attributed to late-stage diagnoses, lack of access to a GP or regular screening, and a fear and mistrust of the healthcare system, due to a long history or racism and discrimination, which creates a hesitancy to seek medical help.

To break down these barriers and create trauma-informed treatment plans to improve Indigenous patient outcomes, BC Cancer has hired IPNs at all six BC Cancer centres.

“Medical institutions, similar to education and every other Western institution, were not created for Indigenous people, or with our success and safety in mind,” says Monica Gerow, who has been in her IPN role at BC Cancer – Kelowna for just over a year.

And a cancer diagnosis, and the resulting onslaught of medical appointments, while overwhelming for anyone, she adds, is even more daunting for an Indigenous person.

“When you add the history of residential schools, Indian hospitals, the Sixties Scoop — add that much generational trauma into somebody’s life — and then expect them to enter these spaces, it’s just a different experience entirely.”

Monica typically balances a dozen patients at a time at BC Cancer – Kelowna. Support includes phone calls to check-in, arranging transportation or accommodation for out-of-town patients, helping with connections to the First Nations Health Authority and Métis Nation BC, and facilitating access to financial aid.

A few of her patients have been from Lytton, B.C., which was devastated by forest fires in the summer of 2021 and then cut off again by flooding just over four months later. Their needs — having access to a grocery store for food, or ensuring an ambulance would be able to get to them — required Monica to help establish a local support network of friends, family and health care providers post-treatment. “It’s hard to let people head back home to somewhere that’s not a community anymore,” she says.

Monica Gerow is an Indigenous Patient Navigator at BC Cancer – Kelowna.

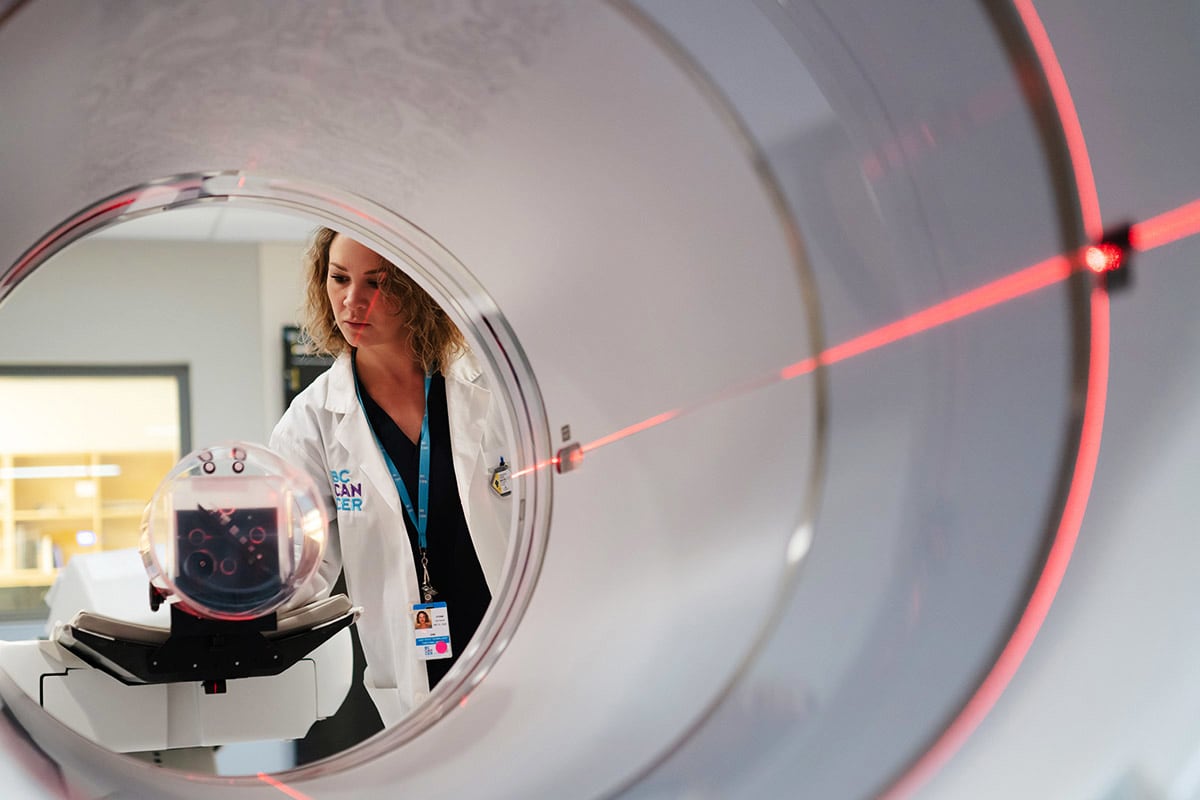

Other times, her role requires her to be there physically, attending appointments and providing emotional support. “It’s sometimes just as simple as sitting with someone while they’re waiting for their radiation treatment, or holding someone’s hand as you walk them to their CT scan. Many patients are residential school survivors, who have a history of being abused by doctors, so entering these spaces is triggering and re-traumatizing,” she says.

Providing connections to the land (Monica has walked patients down to the lake after they mentioned water was important to their wellbeing) holding prayer ceremonies, or other ceremonies such as smudging are also an important part of culturally safe care.

Monica, whose family hails from Saskatchewan’s Cote First Nation, says the local Westbank First Nation, and other Okanagan Nation communities, have been incredibly welcoming and open to teaching her about B.C. cultural ceremonies such as cedar brushing.

The ceremony, in which a practitioner brushes a patient with a cedar branch to heal and protect, was new to her, but is a common spiritual care practice among some B.C. First Nations.

“Indigenous communities really value holistic approaches. When looking at an illness it’s so important to also take care of our minds, our spirit and our emotional state. Offering that kind of spiritual care throughout their treatment journey gives Indigenous people that extra push to keep going,” she says.

For Crystal Harper, the necessity of spiritual care in the Indigenous cancer journey hits close to home. Her dad, a member of the Lil’wat First Nation, was diagnosed with liver cancer in April 2021. He passed away in July last year, just three weeks after she’d started her job as an IPN at BC Cancer – Vancouver.

“One of the last things he said to me was how proud he was of me for doing this,” says Crystal. “He pushed for me to be the voice for Indigenous people because of what he experienced. He had a hard time accessing care, even getting prescriptions filled, and it caused him a lot of unnecessary stress. One thing he really wanted was to have access to elder support.”

Elders play a key role in Indigenous communities. As knowledge keepers they ensure cultural continuity and can serve as teachers, healers, advisors and counsellors. “They offer ceremony such as smudging, prayer, even drumming and singing, and they really do help uplift patients,” Crystal says.

Currently, BC Cancer doesn’t have access to full-time elder support for patients but it’s something that Crystal is hoping will become ingrained in the Indigenous Cultural Safety program in the future. She’s also working towards creating an Indigenous support circle for patients and their families.

“Indigenous peoples need to have that safe space to come together and speak about their journey with one another. Connecting with others on the same journey helps them to feel like they’re not alone.”

Since Crystal doesn’t have dedicated office space at BC Cancer – Vancouver, she usually checks in with patients over the phone, or meets with them off-site to coordinate access to health care programs and services or address cultural or spiritual care needs.

Traditional medicine bundles, containing sage, cedar, sweet grass and tobacco, that IPN Crystal Harper gifts to Indigenous patients.

When connecting with patients and their families, Crystal gifts them with a small medicine bundle which holds the four traditional medicines: sage, cedar, sweet grass and tobacco. “Having these sacred medicines in hand while receiving treatments in a colonial system, and in a place that is far from home and community, helps to give a strong mental, emotional and spiritual connection to family, land and ancestors,” she says.

For one patient in her 70s, from a small isolated community, and alone in Vancouver for treatment during the pandemic, Crystal ended up being a lifeline. “I called her every week, gave her space to speak about herself and her journey, stories from her past, and it was kind of like talking to a family member.”

A residential school survivor, the woman was incredibly fearful of receiving treatments as well as the COVID-19 vaccine. Crystal was able to visit with her, and gently explain the importance of both, especially the vaccine which would allow her to travel home more easily to stay connected with family.

Interactions like these can be hard, Crystal says, because they remind her of what her father went through. “But also it’s rewarding being able to be somebody in the position to help people that need that extra support.”

For an Indigenous person, having another Indigenous persons help you navigate the system is game-changing, says Crystal. “I have lived experience — my mother endured Indian day school and my grandmother attended residential school, as did my other relatives — which helps me connect with patients and their families.

Monica agrees, “I see the relief on people’s faces when they’re offered a referral to an Indigenous person, when I hold space for them culturally, when we’re able to smudge — it means finally being able to breathe in those spaces, and allows them to just focus on their cancer journey.”

To learn more, or to donate to support the work of Indigenous Patient Navigators or the Indigenous Cultural Safety project at BC Cancer, please contact Lindsay Abbott at Lindsay.Abbott@bccancer.bc.ca or 604.839.3626.